OTHERS

Pleural Effusion

This is the abnormal accumulation of fluids between the layers of the pleura- the thin membrane lining the lungs and the inside of the chest cavity. The pleura normally contains a small amount of fluid to lubricate the surfaces as the lungs expand and contract during breathing. However, when excess fluid builds up, it can compress the lungs and cause difficulty breathing, chest pain, and other symptoms. Pleural effusion can be caused by a variety of conditions, including infections, heart failure, cancer, and liver or kidney disease.

- Transudative Effusion: This type of effusion results from systemic conditions that affect the balance of pressure in the blood vessels or the amount of protein in the blood, such as heart failure or liver cirrhosis. The fluid is usually clear and low in protein.

- Exudative Effusion: This type is caused by local factors such as inflammation, infection, or malignancy that increase the permeability of the pleura. Exudative effusions are often associated with infections like pneumonia, tuberculosis, or lung cancer. The fluid is often cloudy and rich in proteins and cells.

- Hemothorax: This refers to the accumulation of blood in the pleural space, usually due to trauma or surgery.

- Chylothorax: This type of pleural effusion involves the accumulation of lymphatic fluid (chyle) in the pleural space, often due to damage to the thoracic duct, the main lymphatic vessel.

The diagnosis of pleural effusion typically involves a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging, and laboratory analysis.

- Physical Examination: Doctors may detect pleural effusion by noting decreased breath sounds, dullness to percussion, or reduced chest movement on the affected side during a physical exam.

- Chest X-ray: A chest X-ray is usually the first imaging study performed and can reveal the presence of fluid in the pleural space. It may show a “meniscus” or curved line of fluid in the lower lung fields.

- Ultrasound: This is useful in identifying and quantifying fluid in the pleural space. It can also help guide thoracentesis (fluid removal).

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: A CT scan provides a more detailed image of the pleural space and surrounding tissues. It is particularly helpful in detecting underlying lung disease, pleural thickening, or masses.

- Thoracentesis: A diagnostic procedure where a needle is inserted into the pleural space to remove fluid for analysis. This fluid is then tested for protein, glucose, cell counts, bacteria, and cancer cells to help determine the cause of the effusion.

- Blood Tests: Blood tests, such as tests for infection, kidney and liver function, and markers of inflammation, may help identify systemic conditions contributing to the effusion.

The treatment of pleural effusion depends on the underlying cause, the severity of symptoms, and the type of effusion.

- Thoracentesis: This is the first-line treatment for large or symptomatic pleural effusions. It involves draining the fluid from the pleural space using a needle or catheter. It provides rapid relief from symptoms such as shortness of breath and allows for fluid analysis.

- Chest Tube Drainage: In cases of large, recurrent, or infected effusions (such as empyema), a chest tube may be inserted to drain the fluid continuously.

- Pleurodesis: For recurrent pleural effusions, especially in cancer patients, pleurodesis may be performed. This involves instilling a chemical irritant (e.g., talc) into the pleural space to cause inflammation and adhesion of the pleura, preventing further fluid accumulation.

- Surgery (Pleurectomy or Decortication): In some cases of persistent or complicated effusions, surgery may be required to remove the pleura or thickened membranes that are trapping the lung.

- Treatment of Underlying Cause: Managing the underlying condition is key to treating pleural effusions. For example:

- Heart failure: Diuretics and medications to manage heart function can reduce fluid buildup.

- Infection: Antibiotics are used to treat bacterial infections causing empyema or parapneumonic effusion.

- Cancer: Chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery may be necessary to treat malignancies causing the effusion.

- Indwelling Pleural Catheter: For patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion who are not suitable for pleurodesis, an indwelling catheter can be placed for home drainage to manage symptoms.

The prognosis of pleural effusion depends on the underlying cause and how promptly and effectively the effusion is treated.

- Heart Failure: Effusions related to heart failure generally respond well to medical treatment, with a good prognosis if the underlying condition is well-managed.

- Infection: For effusions caused by infections such as pneumonia or tuberculosis, timely treatment with antibiotics or antitubercular drugs can lead to full recovery. However, delayed treatment may result in complications like empyema.

- Cancer: Pleural effusions caused by malignancy, especially metastatic cancers, tend to recur and are often associated with a poorer prognosis. However, treatment such as pleurodesis or indwelling catheter placement can help manage symptoms and improve quality of life.

Complications

While pleural effusion treatment is generally safe, complications can occur, particularly with invasive procedures.

- Infection: Infections can occur after procedures like thoracentesis or chest tube placement, though this is relatively rare with proper sterile technique.

- Pneumothorax: Air can accidentally enter the pleural space during thoracentesis, causing a collapsed lung (pneumothorax). This may require chest tube insertion to re-expand the lung.

- Re-expansion Pulmonary Edema: Rapid removal of large amounts of pleural fluid can sometimes lead to fluid accumulation in the lung tissue (pulmonary edema), which may cause respiratory distress.

- Empyema: An untreated or improperly treated infection can lead to empyema, where pus accumulates in the pleural space. This requires drainage and antibiotics.

- Fibrosis and Trapped Lung: In long-standing effusions, the pleura may thicken or scar, causing the lung to become “trapped” and unable to fully expand. This condition may require surgery to release the lung.

Prevention

Preventing pleural effusion involves managing the underlying conditions that can lead to fluid accumulation in the pleural space.

- Heart Failure Management: Proper management of heart failure with medications such as diuretics, ACE inhibitors, or beta-blockers can help prevent the development of pleural effusions.

- Infection Control: Timely treatment of lung infections (e.g., pneumonia or tuberculosis) with antibiotics or antitubercular therapy reduces the risk of effusion formation.

- Cancer Treatment: In cancer patients, early detection and treatment of pleural involvement can help prevent recurrent malignant effusions. This may involve chemotherapy, radiation, or surgical interventions.

- Avoiding Trauma: Preventing chest trauma, which can lead to hemothorax or pneumothorax, can reduce the risk of pleural effusions.

- Regular Monitoring: In patients with chronic conditions such as heart failure or kidney disease, regular medical check-ups and imaging studies can detect fluid buildup early, allowing for prompt treatment and preventing effusion from worsening.

Silicosis

Silicosis is a chronic lung disease caused by the inhalation of crystalline silica dust, typically found in construction, mining, and manufacturing industries. Over time, the inhalation of silica particles causes inflammation and scarring (fibrosis) of lung tissue, leading to impaired lung function. Silicosis is a type of pneumoconiosis and is considered an occupational lung disease. It can range from mild to severe and is often progressive, particularly with prolonged or intense exposure.

- Chronic Silicosis: The most common form, occurring after long-term (typically 10-30 years) exposure to low levels of silica dust. It is characterized by the formation of small nodules in the lungs.

- Accelerated Silicosis: Develops after shorter, more intense exposure (5-10 years) and progresses more rapidly than chronic silicosis.

- Acute Silicosis: Results from very high exposure to silica dust over a few months to years. It progresses rapidly and can cause severe inflammation and fluid buildup in the lungs.

Diagnosing silicosis involves a combination of a detailed occupational history, physical examination, imaging studies, and sometimes lung function tests.

- Occupational History: The key to diagnosing silicosis is identifying a history of exposure to silica dust in high-risk industries, such as mining, construction, masonry, or foundry work.

- Physical Examination: Symptoms include shortness of breath, cough, and sometimes chest pain. In advanced cases, physical findings may include cyanosis (bluish skin due to lack of oxygen), clubbing of fingers, or signs of respiratory distress.

- Chest X-ray: X-rays are commonly used to detect lung nodules or scarring (fibrosis) associated with silicosis. In advanced stages, a “ground-glass” appearance or egg-shell calcification of lymph nodes may be visible.

- High-Resolution CT Scan: CT scans provide more detailed images of the lungs and are used to identify the pattern and extent of fibrosis. This is particularly helpful in diagnosing early-stage or complicated cases of silicosis.

- Pulmonary Function Tests: Lung function tests can measure the capacity of the lungs to hold and move air. Patients with silicosis often have restrictive lung disease, meaning their lungs cannot expand fully.

- Bronchoscopy and Lung Biopsy: In rare cases, a bronchoscopy or biopsy may be required to examine lung tissue and confirm the presence of silica particles.

There is no cure for silicosis, and treatment focuses on managing symptoms, slowing disease progression, and preventing complications. The primary goal is to reduce further exposure to silica and manage lung function.

Avoid Further Exposure: The most critical step in managing silicosis is to stop exposure to silica dust. Workers should be reassigned to areas with no silica exposure or leave the workplace altogether.

- Bronchodilators: Inhalers may be prescribed to help open airways and improve breathing.

- Corticosteroids: In some cases, steroids are used to reduce lung inflammation.

- Antibiotics: Patients with silicosis are more prone to lung infections like pneumonia or tuberculosis and may require antibiotics.

- Oxygen Therapy: In advanced cases, patients with significant lung impairment may need supplemental oxygen to ease breathing and improve oxygen levels.

- Pulmonary Rehabilitation: A structured program of exercise and education can help improve physical stamina and reduce breathlessness.

- Lung Transplantation: For end-stage silicosis where lung function is severely compromised, lung transplantation may be considered.

- Tuberculosis (TB) Prophylaxis: Since silicosis increases the risk of TB, patients may be given preventive treatment if TB exposure is suspected.

Silicosis is a progressive disease, and while treatment can alleviate symptoms and slow progression, it typically worsens over time, especially if exposure to silica continues.

Prognosis

- Chronic Silicosis: Patients with mild chronic silicosis may live for many years with manageable symptoms if exposure to silica is eliminated. However, chronic silicosis can progress slowly and lead to disability over time.

- Accelerated and Acute Silicosis: These forms progress rapidly and often lead to respiratory failure within a few years of diagnosis. Acute silicosis, in particular, can be life-threatening without immediate intervention.

- Increased Risk of TB and Lung Cancer: Silica exposure is linked to a higher risk of developing tuberculosis and lung cancer, further impacting life expectancy and quality of life.

Complications

- Tuberculosis (TB): Silicosis significantly increases the risk of developing tuberculosis due to impaired lung immunity. Regular screening and treatment for TB are critical in silicosis patients.

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): Long-term exposure to silica dust can lead to the development of COPD, which causes persistent obstruction of airflow and worsening respiratory symptoms.

- Lung Cancer: Silica is classified as a carcinogen, and long-term exposure increases the risk of developing lung cancer, especially in smokers.

- Progressive Massive Fibrosis (PMF): In advanced cases of silicosis, large masses of fibrotic tissue (PMF) can develop in the lungs, leading to severe respiratory impairment and disability.

- Respiratory Failure: End-stage silicosis can cause severe scarring and fibrosis in the lungs, leading to respiratory failure where the lungs can no longer provide adequate oxygen to the body.

- Preventing silicosis is essential and relies on controlling silica dust exposure in high-risk workplaces. Measures include:

- Engineering Controls: Employers should implement ventilation systems, dust suppression techniques (such as water sprays), and isolation of dust-producing activities.

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Workers exposed to silica dust should use appropriate respiratory protection, such as N95 or higher-grade respirators.

- Workplace Monitoring: Regular air quality monitoring in the workplace can help identify dangerous levels of silica dust and ensure compliance with safety standards.

- Regular Health Screening: Workers in high-risk industries should undergo regular medical check-ups, including chest X-rays and lung function tests, to detect early signs of silicosis.

- Education and Training: Employers should provide education on the dangers of silica exposure and train workers on how to reduce their risk of inhalation.

- Quit Smoking: Smoking significantly increases the risk of lung damage and complications in workers exposed to silica. Quitting smoking can reduce the risk of lung cancer and improve overall lung health.

Asbestosis

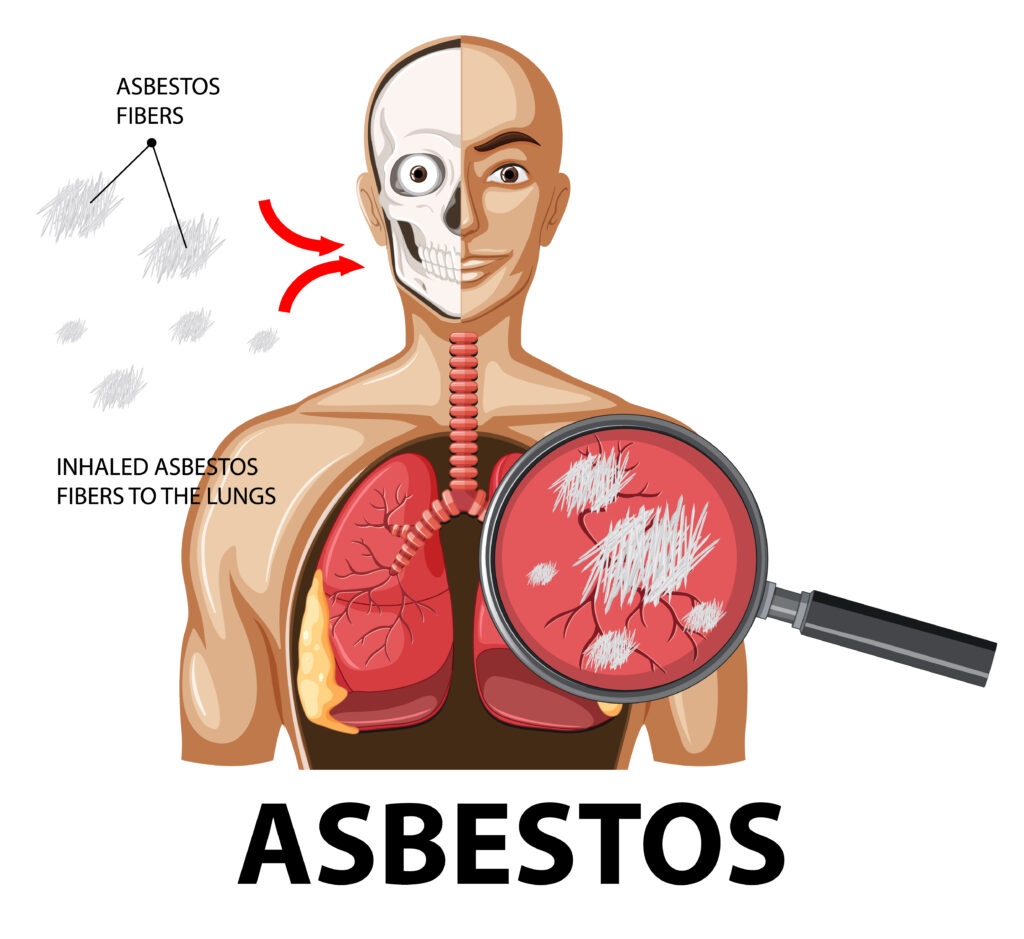

Asbestosis is a chronic lung disease caused by prolonged inhalation of asbestos fibers, which are naturally occurring minerals once widely used in construction, shipbuilding, and other industries due to their heat resistance and insulating properties. Over time, inhaled asbestos fibers cause scarring (fibrosis) in the lungs, leading to breathing difficulties and reduced lung function. Asbestosis can take decades to develop, and while it is a non-cancerous condition, it significantly increases the risk of developing serious conditions like lung cancer and mesothelioma (a cancer of the lining around the lungs). Asbestosis typically occurs in people who have worked in industries where asbestos exposure was common, such as construction, mining, shipbuilding, and insulation manufacturing. It usually takes years or even decades of exposure for the disease to develop.

Asbestos Fibers: Asbestos refers to a group of six naturally occurring fibrous minerals. The fine fibers, when inhaled, can become lodged in lung tissue, causing chronic inflammation and scar tissue formation. These fibers are resistant to being broken down by the body, which leads to progressive lung damage over time.

Lung Scarring (Fibrosis): As the body attempts to clear asbestos fibers from the lungs, it creates scar tissue, which stiffens the lungs and impairs their ability to expand and contract during breathing. This leads to symptoms such as shortness of breath, persistent dry cough, and chest tightness.

The diagnosis of asbestosis involves a combination of medical history, imaging studies, and lung function tests.

- Occupational History: The first step in diagnosing asbestosis is a detailed history of exposure to asbestos, particularly in high-risk occupations. Patients with asbestosis often report years of working in environments with poor ventilation or where asbestos-containing materials were handled without protective equipment.

- Symptoms

Common symptoms include,

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea), especially with exertion

- Persistent dry cough

- Chest tightness or pain

- Fatigue

- Finger clubbing (widening and rounding of the fingertips) in severe cases

- Chest X-ray: A chest X-ray may show classic signs of asbestosis, including scarring (fibrosis) in the lower regions of the lungs. It may also reveal pleural plaques (thickened areas of the pleura) or pleural effusion, which are commonly associated with asbestos exposure.

- High-Resolution CT Scan (HRCT): A CT scan provides more detailed images of the lungs and can detect early fibrosis or other asbestos-related lung abnormalities that may not be visible on an X-ray. HRCT is particularly useful for identifying pleural thickening and interstitial fibrosis.

- Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs): Lung function tests measure how well the lungs are working. Patients with asbestosis often have a restrictive pattern, meaning their lung capacity is reduced. PFTs can assess the severity of the disease by measuring how much air the patient can inhale and exhale, as well as how efficiently their lungs transfer oxygen into the bloodstream.

- Biopsy (Rarely Needed): In rare cases, a lung biopsy may be performed to confirm the presence of asbestos fibers in lung tissue. This is typically not required if imaging and occupational history strongly suggest asbestosis.

There is no cure for asbestosis, and treatment is primarily focused on relieving symptoms, slowing disease progression, and managing complications.

- Avoid Further Exposure: The most important step in managing asbestosis is to eliminate any further exposure to asbestos. Patients should avoid environments with asbestos and take precautions if removal or disturbance of asbestos materials is necessary.

- Medications

- Bronchodilators: Inhalers may be prescribed to open airways and reduce shortness of breath.

- Corticosteroids: In some cases, corticosteroids are used to reduce lung inflammation, although their effectiveness in asbestosis is limited.

- Antibiotics: These may be necessary to treat respiratory infections, which patients with asbestosis are more prone to developing.

- Oxygen Therapy: Patients with severe asbestosis and reduced blood oxygen levels may require supplemental oxygen to help them breathe more comfortably and maintain proper oxygenation.

- Pulmonary Rehabilitation: Pulmonary rehabilitation programs offer exercise training, breathing exercises, and education to help patients improve their physical stamina and manage respiratory symptoms more effectively.

- Lung Transplantation: For patients with end-stage asbestosis and severe respiratory failure, lung transplantation may be an option, although it is considered only in very advanced cases.

The prognosis for asbestosis depends on the severity of lung scarring and the overall health of the patient. While the disease progresses slowly in many cases, it can lead to serious complications over time.

Prognosis

- Mild to Moderate Asbestosis: Patients with mild or moderate disease may live many years with manageable symptoms, especially if further asbestos exposure is avoided. However, lung function tends to decline over time.

- Severe Asbestosis: In severe cases, patients may develop significant lung impairment and complications such as respiratory failure. This can lead to a poor quality of life and reduced life expectancy.

- Increased Cancer Risk: Asbestosis significantly increases the risk of developing asbestos-related cancers, including lung cancer and mesothelioma, both of which have poor prognoses.

Complications

- Lung Cancer: Asbestos exposure is a known cause of lung cancer, particularly in individuals who smoke. The combination of asbestosis and smoking greatly increases the risk of developing lung cancer.

- Mesothelioma: This is a rare but aggressive cancer of the lining of the lungs (pleura) or abdomen (peritoneum) caused almost exclusively by asbestos exposure. Mesothelioma is typically diagnosed at an advanced stage and has a poor prognosis.

- Pulmonary Hypertension: As the scarring in the lungs worsens, it can lead to increased pressure in the pulmonary arteries (pulmonary hypertension), making it harder for the heart to pump blood through the lungs.

- Cor Pulmonale: Chronic lung diseases like asbestosis can strain the right side of the heart, leading to cor pulmonale (right-sided heart failure). This occurs when the heart is unable to pump blood effectively due to increased resistance from damaged lungs.

- Respiratory Infections: Patients with asbestosis are more prone to developing respiratory infections, such as pneumonia, which can worsen their lung function.

- Pleural Disease: Asbestos exposure can lead to pleural plaques (localized thickening of the pleura) or pleural effusions (fluid buildup around the lungs), which can cause additional breathing difficulties.

Preventing asbestosis requires strict control of asbestos exposure, especially in high-risk industries. Measures include,

- Workplace Safety: Employers should implement engineering controls, such as proper ventilation, dust suppression systems, and isolation of asbestos-containing materials. Employers should also monitor air quality and comply with asbestos safety regulations.

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Workers exposed to asbestos should use appropriate respiratory protection (e.g., high-efficiency particulate air [HEPA] filters) to minimize inhalation of asbestos fibers.

- Asbestos Removal Protocols: When asbestos materials need to be removed or disturbed, certified asbestos abatement professionals should follow proper safety protocols to prevent the release of fibers into the air.

- Regular Health Screening: Workers exposed to asbestos should undergo regular medical check-ups, including lung function tests and chest imaging, to detect early signs of asbestosis or other asbestos-related diseases.

- Quit Smoking: Since smoking greatly increases the risk of lung cancer in individuals exposed to asbestos, quitting smoking is one of the most important preventive measures for workers with past or ongoing asbestos exposure.

- Public Awareness: Educating workers and the public about the dangers of asbestos and how to prevent exposure is crucial in reducing the incidence of asbestosis and other asbestos-related diseases.

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory disease characterized by the formation of small clusters of immune cells called granulomas in various organs, most commonly the lungs and lymph nodes. These granulomas can affect how the organs function. Sarcoidosis can be acute, with sudden onset and resolution, or chronic, with long-term effects. While the exact cause is unknown, it is believed to be related to an overreaction of the immune system to an unknown trigger, possibly infectious or environmental agents. Sarcoidosis often affects the lungs, but it can also impact the skin, eyes, heart, and other organs.

Sarcoidosis most often affects adults between the ages of 20 and 40. It is more common in African Americans, Scandinavians, and women. There may be a genetic predisposition, but environmental factors may also play a role.

Granulomas Formation: In sarcoidosis, the immune system reacts abnormally by forming granulomas (small clusters of immune cells) in affected tissues. These granulomas can disrupt the normal structure and function of the organ, leading to symptoms and complications.

Organs Involved: While sarcoidosis can affect any organ, the most commonly involved organs are:

Lungs: This is the most common site, and when sarcoidosis affects the lungs, it is known as pulmonary sarcoidosis.

Lymph Nodes: Swelling of the lymph nodes, particularly in the chest, is common.

Skin: Sarcoidosis can cause skin rashes or lesions.

Eyes: Sarcoidosis can cause inflammation in the eyes (uveitis).

Heart and Nervous System: In rare cases, it can affect the heart (cardiac sarcoidosis) or the nervous system (neurosarcoidosis).

Diagnosis of sarcoidosis is challenging as the symptoms can vary widely depending on the organ affected. A combination of medical history, physical examination, imaging, and biopsy is often required.

- Medical History & Physical Examination: Doctors will evaluate symptoms such as shortness of breath, persistent dry cough, skin rashes, eye irritation, or swollen lymph nodes. A detailed medical history and family history are important, as sarcoidosis can mimic other conditions like tuberculosis or lymphoma.

- Chest X-ray: This is often the first test performed. In over 90% of cases, chest X-rays will show enlarged lymph nodes in the chest or abnormalities in the lung tissue, such as fibrosis or nodules.

- High-Resolution CT Scan: A CT scan provides more detailed images of the lungs and other organs, which helps identify the extent and pattern of the disease.

- Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs): In cases where the lungs are involved, PFTs are used to assess how well the lungs are functioning. These tests measure the amount of air the lungs can hold and how effectively they transfer oxygen into the bloodstream.

- Biopsy: A biopsy is often needed to confirm sarcoidosis. It involves taking a small sample of tissue from the affected organ (such as the lungs, skin, or lymph nodes) to check for the presence of granulomas.

- Blood Tests: Blood tests can help assess the overall health of the patient and look for markers of inflammation. Increased calcium levels (hypercalcemia) and elevated levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) are common in sarcoidosis.

- Bronchoscopy: If the lungs are affected, a bronchoscopy may be performed to collect samples of lung tissue or fluid for analysis.

- Eye Examination: If sarcoidosis is suspected to affect the eyes, a thorough eye exam is conducted to detect any inflammation or damage.

Treatment for sarcoidosis depends on the severity and organs involved. In many cases, the condition resolves on its own without treatment, but more severe cases require medication.

- Observation: Many patients with mild sarcoidosis do not need treatment, especially if the disease does not cause significant symptoms or organ damage. Regular monitoring is essential to ensure the disease does not progress.

- Corticosteroids: The mainstay of treatment for sarcoidosis is corticosteroids, such as prednisone. Steroids help reduce inflammation and prevent granulomas from causing further damage. However, long-term use of steroids can have side effects, so doctors aim to use the lowest effective dose for the shortest time.

- Immunosuppressive Medications: If corticosteroids are not effective or cause significant side effects, other medications that suppress the immune system, such as methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate, may be prescribed.

- Biologic Therapies: In more severe or refractory cases, biologics such as TNF inhibitors (e.g., infliximab) can be used to target the immune system more specifically.

- Pulmonary Sarcoidosis: In addition to corticosteroids, oxygen therapy may be needed in advanced lung disease. Lung transplantation is considered in end-stage cases.

- Cardiac Sarcoidosis: Patients with heart involvement may require pacemakers, defibrillators, or other treatments to manage heart arrhythmias.

- Ocular Sarcoidosis: Eye drops containing corticosteroids or other medications may be prescribed to manage eye inflammation.

- Physical Therapy & Pulmonary Rehabilitation: For patients with significant lung involvement, pulmonary rehabilitation and physical therapy can improve quality of life by increasing physical fitness and respiratory function.

Sarcoidosis has a variable prognosis depending on the organs involved and the severity of the disease. While many cases resolve on their own or with treatment, others can lead to chronic illness and complications.

Prognosis

- Mild Sarcoidosis: In about half of the cases, sarcoidosis resolves without treatment within 1 to 2 years. These patients often have minimal long-term issues.

- Chronic Sarcoidosis: Some patients develop chronic sarcoidosis that requires long-term management. Chronic disease can lead to permanent organ damage, particularly in the lungs, heart, and nervous system.

- Severe Sarcoidosis: Severe cases, especially those involving the heart or nervous system, can be life-threatening.

Complications

- Pulmonary Fibrosis: Long-term inflammation in the lungs can lead to pulmonary fibrosis, a condition in which scar tissue forms, making it difficult for the lungs to function properly. This can cause progressive breathing difficulties and may lead to respiratory failure.

- Heart Problems: Cardiac sarcoidosis can lead to arrhythmias, heart failure, or sudden cardiac death. This is a serious complication and requires careful monitoring and treatment.

- Eye Damage: Untreated ocular sarcoidosis can lead to vision loss if the inflammation affects critical parts of the eye.

- Hypercalcemia: Elevated calcium levels in the blood or urine can occur due to the abnormal immune activity in sarcoidosis, leading to kidney stones or kidney damage.

- Neurological Sarcoidosis: In rare cases, the nervous system can be affected, leading to neurological symptoms such as seizures, headaches, or neuropathy (nerve pain or dysfunction).

- Increased Risk of Infections: Long-term use of immunosuppressive medications can increase the risk of infections due to a weakened immune system.

There is no known way to prevent sarcoidosis since its exact cause remains unclear. However, individuals at higher risk (e.g., those with a family history of sarcoidosis or who work in environments with potential immune triggers) can take steps to monitor their health.

- Avoiding Environmental Triggers: While the exact triggers of sarcoidosis are not known, reducing exposure to environmental agents such as dust, chemicals, and infectious agents may help lower the risk.

- Early Detection & Monitoring: Regular medical check-ups and early evaluation of symptoms such as persistent cough, shortness of breath, or skin rashes can help detect sarcoidosis early and prevent complications.

- Healthy Lifestyle: Maintaining a healthy immune system through a balanced diet, regular exercise, and avoiding smoking may reduce the severity of the disease if it develops.